AUSTRALIA’S native freshwater eel tailed catfishes include several members of the Family Plotosidae that have evolved over millenia to survive in the harsh and unpredictable environments of Australia’s inland waters.

The best known species on the east coast is the eel tailed catfish Tandanus tandanus, which occurs in coastal rivers along the eastern seaboard from the Hunter River north to central Queensland, as well as throughout the Murray-Darling river basin. Also known as dewfish, or freshwater jewfish, the abundance of T. tandanus has become regarded as a reliable indicator of environmental health.

Although once widespread and very common in eastern Australia, T. tandanus populations have suffered severe declines in not only the Murray-Darling Basin, but also in many coastal river drainages. Indeed, this species is now considered endangered in the Murray Darling Basin and NSW, threatened in Victoria and endangered (and fully protected) in South Australia.

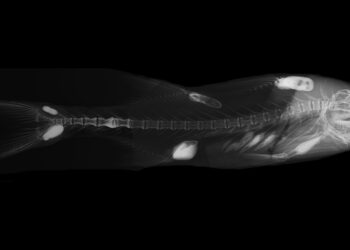

Eel tailed catfish have a distinctive body layout, with a broad head, stocky body and large underslung mouth surrounded by thick fleshy lips and four pairs of sensory barbels (or whiskers). Their most distinctive features include the eel-like tail and strong barbed spines on the dorsal and pectoral fins, the latter which can inflict nasty wounds to unsuspecting anglers. Like their namesake, eel tailed catfish also have slimy, scaleless eel-like skin. Their eyesight is average but their senses of taste and smell are quite acute, which assists them with locating natural dietary items which consist mainly of yabbies, shrimps, molluscs, smaller fishes and any other bottom dwelling food items befitting of an opportunistic carnivore.

For some time scientists suspected, based on both morphological and genetic evidence, that T. tandanus was actually at least three different species. The eeltailed catfish from the Murray Darling basin and coastal rivers of southern Queensland was considered the typical T. tandanus, while undescribed, very closely related species were suspected to occur in some east flowing river catchments in northern NSW (Bellinger, Macleay, Hastings and Manning Rivers), and in northeastern Queensland (Daintree, Mulgrave-Russell, Johnstone, and Tully Rivers).

The northern species has recently (2014) been described as the wet tropics tandan (Tandanus tropicanus), while the catfish from northern NSW are considered to be undescribed species of “Bellinger catfish”. The only other species of Tandanus described from Australia at this time is the freshwater cobbler T. bostocki, from south western WA.

Tandanus tandanus can be found in a wide range of freshwater habitats including rivers, creeks, lakes, impoundments, billabongs and lagoons. In faster flowing rivers they appear to prefer the deeper, slow flowing pools. Electronic tagging studies from the Murray Darling Basin have shown that this species is non migratory, and spend much of their time in and around snags and underwater vegetation foraging within a relatively limited home range of usually less than 500 meters. Tagging also showed that T. tandanus were more active at night, with greater movement of female fish at night compared to males.

This species grows relatively fast, and they become sexually mature at between three and five years old (800g – 1.2 kg). Spawning occurs during spring and summer when water temperatures rise to between 20 and 24°C. During spawning male and female catfish pair up. One to two weeks before spawning the male builds a circular nest up to two metres in diameter on a gravel or rocky bottom.

The nest usually contains a central depression into which females can lay up to 20,000 large eggs. Usually the male, but sometimes both parents, attend the nest and aerate and protect the eggs until after hatching, which occurs in around seven days at 20°C. More than one spawning may occur during each spawning season. Tandanus tandanus are thought to live to a maximum age of at least 8-10 years, and can grow to a maximum size of around 90 cm, though adult fish are more commonly encountered between 40 and 50 cm long.

A catfish nest. Image: Ben Diggles

Although this species is considered excellent eating and hence is a popular target for recreational anglers, fishing for eel tailed catfish is now prohibited in some states (e.g. South Australia), and heavily restricted in others. This is because of the drastic declines in their populations that have been observed, particularly since the 1970s in the Murray-Darling Basin and more recently in other areas.

Numerous factors are thought to have contributed to the decline of eel tailed catfish populations, including habitat degradation (from river regulation and siltation that severely impacts spawning by smothering eggs and the rocks and pebbles used to build nests), and increased competition with introduced species such as carp.

Thermal pollution causing loss of spawning cues due to cold-water discharge from the base of large dams and high-level weirs is also thought to contribute to declines in catfish populations in some areas, as is pollution caused by runoff of agricultural chemicals. However, in the upper reaches of eastwards flowing rivers in South East Queensland I have personally observed precipitous declines in eel tailed catfish numbers to correlate with arrival of European carp. I think the two species are incompatible as carp have similar foraging habits to catfish, so compete directly for food, but they also are very likely to raid catfish nests, eating the eggs and disrupting catfish recruitment.

The absence of historically prominent catfish nests in areas where carp have recently invaded, in the absence of other obvious habitat changes, is to me sufficient evidence to point the finger to yet another reason why we must halt the advance of carp in Australia.